Most human endeavours are not solitary pursuits. Ric Parkin looks at the interconnection of everyone.

Ah the pleasures of a fine late English spring. After a couple of horribly wet and miserable months, May has ended with some gloriously hot and sunny days, which is just as well as I’ve been sitting in a field drinking a variety of weird and wonderful brews at the 39th Cambridge Beer Festival [ CBF ]. This is a significant event, as it functions as an informal reunion for the region’s IT sector – it seems that large proportion of software developers like their real ale, and so I quite often bump into current and past colleagues and can catch up with what’s happening in the industry. Judging by the range of company t-shirts on display, you get a feel for how big and varied is the local tech-cluster known as ‘Silicon Fen’ [ Fen ].

The origins of this are usually traced to the founding of the UK’s first Science Park back in the early 1970s. By encouraging small high tech startups, often spun out of research from the University, this and many other subsequent business parks in the region have transformed the local (and national) economy, with a critical mass of companies and jobs in sectors such as software and biotech. It’s easy to see how such a cluster effect feeds off itself to breed success. By having so many companies nearby, people are more willing to take a risk and start (or join) a small company, because if it goes under (as many do) it’s easy to get a job elsewhere. There are also lots of small ‘incubators’ such as the St Johns Innovation Centre [ St Johns ] where such companies can get started with lots of advice and help, often from other startups in the next units. Indeed it’s this networking effect that really seems to be key – it’s comparatively easy to find important staff in the area who’ve already been through the experience of turning tiny startups into successful businesses, and the region’s success encourages people to relocate or stay here after university, providing a rich pool of talent. Indeed it was my realisation of this that made me decide to buy a house and settle here – there are so many companies that I wouldn’t have to move in order to change jobs. And I’ve been proved right – in 18 years I’ve been in 7 different jobs, usually with small startups, but am still in the same house.

Such has been the success that people try to recreate the effect – locally there is an attempt to build a biotech cluster, centred around a research campus [ Genome ] (home of the Sanger Institute, one of the pioneers of DNA sequencing and central to the deciphering of the human genome) and Addenbrooke’s Hospital to the south of the city. And recently Google and others have set up an incubator hub in east London, dubbed Silicon Roundabout [ Roundabout ].

But there’s more to it than just bringing companies together. There has to be that networking effect, which can range from bumping into someone from the next door company in the shared canteen of the Incubator building, informal meetups such as the Beer Festival, formal networking sites such as LinkedIn and The Cambridge Network [ Network ], and professional groups such as Software East [ East ] and of course ACCU itself. Some of these will be of more value to you than others depending on what you want to get out of them. Some are good for contacts, some are good for sharing technical experiences, and some are sadly getting plagued by recruiters wanting to connect with you. But I think they all help by expanding your circle of potential experience . By that I mean that if you have something new that you have to do, then you could work things out for yourself but it’d take a long time and you’re likely to make lots of mistakes. But if instead you know someone who’s done it before, then you can take their advice or get them to help you, and your chances of success will be vastly improved.

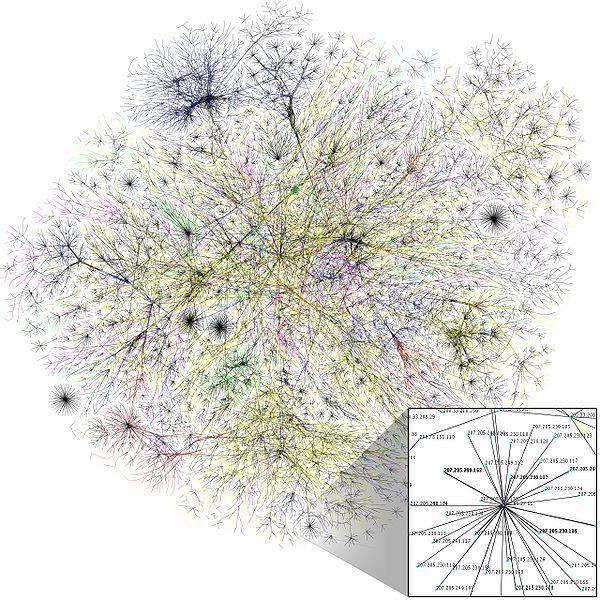

Now we’ve established that pooling experience can increase success, a question is how much of a network do you need? Too much and the effort needed to maintain it will interfere with actually getting on and doing things; too little and you won’t have the contacts for when you need them. Well, the good news is that there is a branch of research called Network Theory [ Theory ] which concerns itself with the properties of networks, such as social interconnectedness. One famous type of network is called a Small-World network, informally known as The Six Degrees Of Separation [ Six ]. (It has also been turned into a game involving Kevin Bacon, apparently after he commented that he’d worked with everyone in Hollywood, or someone who’d worked with them. [ Bacon ]). These types of networks have two defining properties – on average each individual has only a few connections; and yet they can connect with anyone in the entire network with only a few ‘jumps’. The trick is that you have a few key people who connect to a lot of others, especially other key people. Then all you need to do is know a key person, who knows another key person, who knows your target. (Interestingly, there are hints that we have an ‘ideal’ social group size [ Dunbar ]. I wonder if this number is related to how many connections you need for a good small-world network, which would be needed for a successful civilisation to arise). These types of networks appear in many different disciplines, as they are very efficient at creating robust, well connected networks. Examples include neural networks, seismic fault systems, gene interactions, database utility metrics, and the connectedness of the internet (see Figure 1 for a map of the internet from the wikimedia commons [ Internet ]). Its robustness stems from the fact that if you remove an arbitrary node, the mean path length between any two nodes doesn’t tend to change. Problems will only occur if you take out enough key nodes at once).

|

| Figure 1 |

While a wide social and professional network is useful, in our day-to-day work we tend to work in a much smaller team. We rarely work in isolation as it’s not very efficient to do it all yourself – in a similar way to getting advice from a professional connection, we use division of labour and skills to make up a team. For example, instead of me spending ages learning about databases and struggling to support one to the detriment of my programming, we just hire someone who’s a professional DBA. By building such a team we have a group who collectively have all the skills needed.

But now we need to coordinate them. How much of an overhead will that be? Unfortunately models and experience show that this can be disastrously high – by considering a team of N people who all talk to each other, we see that there are ( N -1)! (ie (N-1)x(N-2)x...x2x1) different possible interactions. This gets very big very quickly, which explains why an ideal team size is actually quite low. It has to be large enough to get the benefits of division of labour, but small enough that the overhead of communication and coordination doesn’t swamp people. Five to ten people is usually pretty good. But let us reconsider the assumption that everyone needs to talk to everyone else. If we can arrange things such that you generally don’t need to, then we can have a bigger team with the same overhead.

Small world theory also gives us ideas about how we should be organising them – in small focussed groups with a few key individuals acting as links between the groups. In the past, the groups were often organised by discipline, so for example all the programmers were in one team, the testers in another, sales in another and so on. But this was found to not work very well as the lifecycle of the product cuts across all these teams, whereas there was relatively poor communication channels that mirrored it. Instead, now we tend to make a team with members from all the different disciplines (although things like sales and marketing still tend to be separate from the technical teams – I can see why as a lot of their activities are done after a product is built, but it is a shame that there aren’t at least representatives within the technical teams to give input from their point of view, and to understand the product better). You can then see how the modern technical company structure has arisen, with small multi-disciplinary teams building focussed products, coordinated by a few key communicators. Done well, you can grow this model into a large productive company.

All good things....

I’ve been editing Overload for just over four years now. It been tremendous fun, but all things must come to an end at some point, and that time has come. From next issue there will be a new editor – I’ll leave them to introduce themselves in their own fashion then. I’ll be helping out in the review team, and may even find time to write some new articles, so you have been warned! I’d just like to thank all those who’ve helped make all those issues, from the many authors, the helpful reviewers, Pete’s fantastic covers, and especially Alison’s excellent (and patient) production.

References

[Bacon] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Six_Degrees_of_Kevin_Bacon

[CBF] http://www.cambridgebeerfestival.com/

[Dunbar] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunbar's_number

[East] http://softwareast.ning.com

[Fen] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silicon_Fen

[Genome] http://www.sanger.ac.uk/

[Internet] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Internet_map_1024.jpg

[Network] http://www.cambridgenetwork.co.uk

[Roundabout] http://www.siliconroundabout.org.uk/

[Six] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Six_degrees_of_separation

[SmallWorld] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Small-world_network